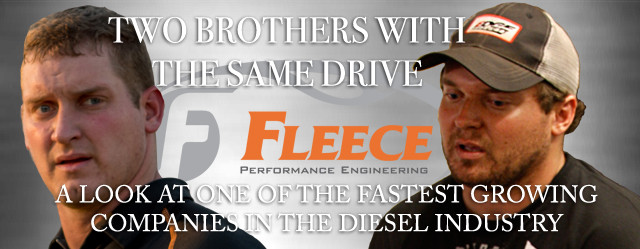

7 SHARES Fleece Performance: A Look At One of Diesel’s Growing Companies

This article was originally published September 28, 2016 by Mike McGlothlin on Diesel Army:

If you’ve spent any amount of time in the diesel industry, chances are pretty good that you’ve heard a turbo referred to as a “Cheetah” at some point. And if you’ve been in the diesel game for the past decade, you probably remember when you started hearing the Fleece Performance name being thrown around.

It’s a company that was formed by brothers Brayden and Chase Fleece, two highly motivated self-starters with a knack for wrenching, tweaking, and making big horsepower with today’s electronically controlled Duramax and Cummins mills. The company started out in a modest, 3,200 square-foot pole barn in rural west-central Indiana, but through innovation, hard work, and determination, would find itself at the forefront of cutting-edge, common rail technology within five years’ time.

They may run a multimillion-dollar company, but you’ll never find Brayden (middle) or Chase Fleece (left) afraid to get their hands dirty. Here you can see them, along with the late Danny Toops (right) finishing up a 48RE transmission swap on a ’06 Dodge—in a parking lot, no less.

In the early days, the Fleece brothers earned a reputation for offering the TurboBrake (an electronic exhaust brake) and upgrading the factory turbocharger found on the LLY Duramax. Along the way, Brayden would develop the AlliLocker and TapShifter — two breakthrough products that continue to be in high demand today. Other areas of expertise that put them on the map included exceptional EFI Live tuning, engine builds, transmission upgrades, and fuel system and driveline improvements. As you can imagine, with so many services being offered out of a 54×60-foot barn, the shop’s limited working space was quickly realized. Big things were happening, but the boys were out of room.

Going from zero-to-60 in what seemed like the blink of an eye, Fleece’s expansive growth all but forced them to upsize the entire operation in 2012. And upsize they did. Relocating to an 18,750 square-foot facility (and later adding another 7,250) in Nitro Alley (Brownsburg, Indiana), the Fleece brothers found themselves in good company and among neighbors such as Schumacher Racing, John Force Racing, and Tony Stewart Racing Enterprises. It was here that Fleece would morph into an all-in-one operation where parts could be designed, manufactured, assembled, and tested completely in-house.

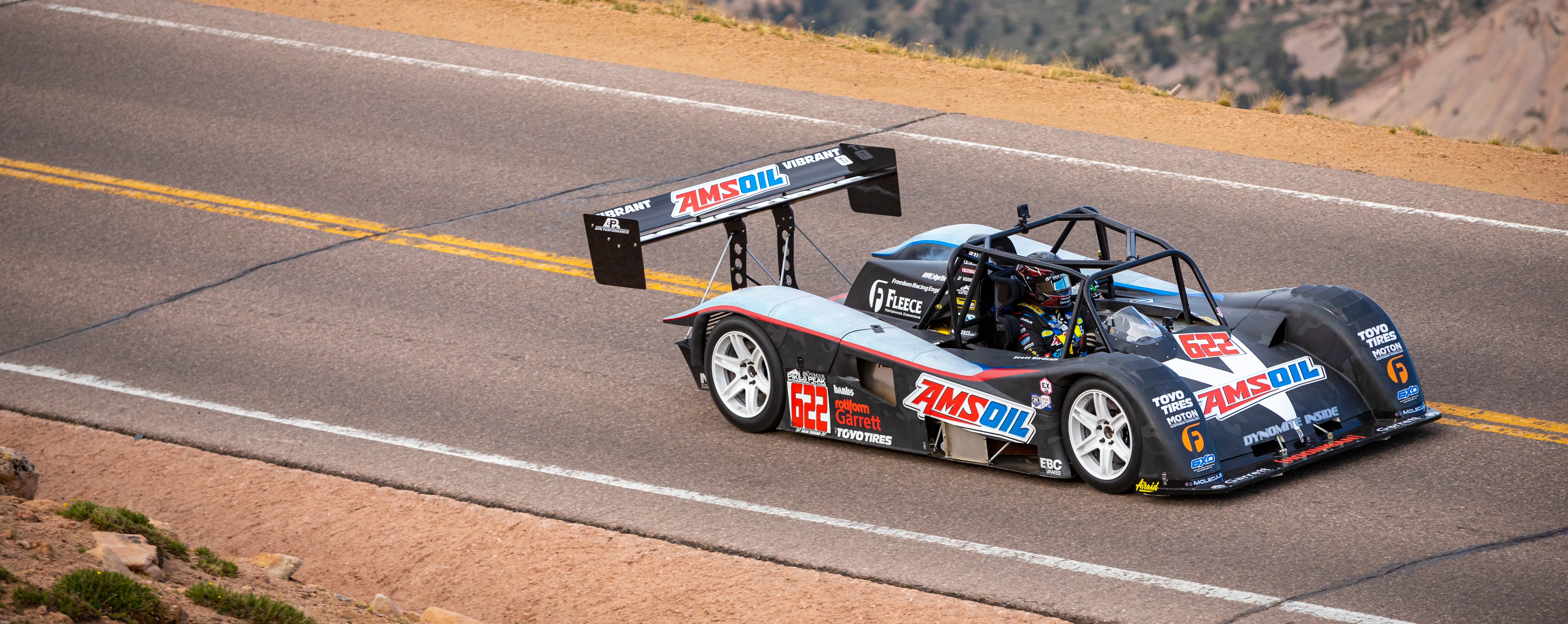

Fleece takes a lot of pride in its Comp 6.4 program. Built at Freedom Racing Engines (a 7,250 square-foot facility obtained in 2014), these race-ready Cummins mills use a 6.7-liter block that incorporates ductile iron sleeves (hence the displacement reduction to 6.4-liter), are unfilled (still circulating coolant), and have proven reliable at more than 2,000 horsepower.

One-on-one With The Brothers

What got you into diesels?

Brayden Fleece: I’ve been into all things mechanical and electronic since I was roughly six or seven years old. My relatives would drop off “junk” radios and electronics and I would take them apart, poke around, and sometimes get them working again. That spilled over into mechanical things. Most were disassembled, never to be reassembled or fixed, but all the while I was learning the fundamentals of wrenching. I soon became the ‘Mr. Fixit’ of the family.

Later, Chase and I were given a go-kart when I was 12 and he was six-years-old. We soon learned that 3.5 horsepower wasn’t going to satisfy our need for speed on Indiana gravel roads, so our grandfather’s garden tiller — unbeknownst to him — became the donor of a 5 hp Briggs and Stratton. We tweaked on that with different sprockets, carbs, and exhaust until we graduated into four wheelers and dirt bikes. Our mechanical knowledge and fundamentals continued to grow as we grew up, and the engines and the need for more power grew as well.

Fast forward a few years to the trucks that got us into this business. Chase had a 2002 Dodge Ram H.O. with a six-speed, and I had just purchased a new 2004.5 Chevrolet 2500HD Duramax LLY.

This is what Brayden spent a lot of his time doing in the early days of Fleece Performance: tuning and then data logging a truck on the chassis dyno with EFI Live software.

What got you guys interested in the electronic side of diesel performance?

BF: We were attending the Scheid Diesel Extravaganza in 2004 as regular show-goers. While walking around in the vendor area we met Patty Haisley at the Haisley Machine booth and she sold us their Torque Enhancer module for Chase’s truck. We noticed an increase in power, but it wasn’t quite what we had hoped for, so we drove up to Fairmount, Indiana to visit Haisley Machine.

Van and Patty gave us the shop tour and then Chase drove her truck equipped with the same module, plus injectors and an aftermarket turbo. We were hooked. She shouldn’t have told us about that little wire in module’s harness that you could clip to gain even more power on the Torque Enhancer module … it was clipped in the driveway. Patty sold him injectors that day as well.

Improving on the factory turbo options found on Duramax and Cummins powered trucks has always been part of the Fleece forte. Take this 63 mm Holset Cheetah for instance. It’s based on the factory Holset HE351CW offered on 2004.5-2007 5.9-liter Cummins engines, but Fleece fits it with a 63 mm billet compressor wheel (versus 58 mm stock) and adds a larger wastegate actuator. Direct, bolt-on installation, quick spool up, and capable of supporting 650 rwhp are this little Cheetah’s key strong suits.

What was the first product you developed?

BF: The first product was the TurboBrake … an electronic exhaust brake that I developed with engineering help from the principals at TST Products in Columbus, Indiana. The product was ahead of its time, not in technology, but in terms of our business and our marketing capabilities. The Cheetah turbo for my LLY truck was the next product we came up with and it was about as different as you could get from the TurboBrake.

The first 30 Cheetahs (the name being a play on the word “cheater”) were produced using a 1940’s South Bend lathe with a leather drive belt. There was no easy way to create a contour on an engine lathe, so it was a tedious process of cutting angles, filing, and smoothing with sandpaper. Clearances were checked with Dykem layout fluid and any high spots were sanded down to create the proper contour and clearance for a larger compressor and turbine wheel. In 2008 we purchased our first piece of equipment, a Haas TL-1 CNC lathe, to machine our turbocharger components on.

In 2014 Fleece purchased Freedom Racing Engines, which along with all the necessary machining equipment for producing high-end, competition engines, came with an engine dynamometer. This means that swapping parts, making ECM tweaks, and collecting back-to-back data can be performed to ensure each power plant the company builds leaves its facility with the best possible chance of winning.

When did things snowball into the pole barn being such a hopping place with 20 trucks parked outside? Was it turbos, injectors, and transmissions at first, or electronics and tuning, or a combination of all of those?

Chase Fleece: All of the above. We had a good base of local customers that spread the word as far away as Montreal! We were also one of the few, if any, shops that were building transmissions with a one-day turnaround. On top of that, we offered in-house tuning, our own turbocharger, and fabrication abilities.

You cover the entire spectrum: you cater to the street truck crowd, drag racers, and competitive sled pullers. Did you intend to cover so many different segments, or did the need for more horsepower in each category simply take you there?

Fleece Brothers: What we have developed for competition has spilled over into the street market over the years. We would never have imagined that a 1,000 rwhp Duramax or Cummins could be so streetable. The horsepower numbers have steadily climbed in the common rail market, and with the parts and tuning currently available the streetability is much better than that of mechanically injected engines.

To complement its turbochargers and allow customers to reap the most performance gains from larger injectors, Fleece offers its own line of CP3 injection pumps for both the Duramax and Cummins. The company’s PowerFlo 750 (shown) features a 10 mm shaft, supports 750 to 800 rwhp, and each unit is tested on an in-house engine simulator and pump test stand for utmost quality control.

In terms of making horsepower with common rails, what were some of the early obstacles you encountered, and what hurdles did you have to overcome to move the bar higher?

Fleece Brothers: The biggest mistake people were making in the early common rail days was not measuring rail pressure. Injectors weren’t performing at the level that they are today, but we were able to easily demand way more than a single OEM CP3 could provide. Dual pumps hit the market and fixed a lot of those issues, but there were still a lot of people applying the “more is better” theory to everything.

We stepped back and looked at what is actually happening when you demand 3000 uS (3,000 microseconds) of injection duration. The goal is to get as much fuel in the cylinder as possible in the shortest time possible. Our theory is to achieve the highest injection rate the system can deliver while maintaining rail pressure. This is why our competition Cummins engines use injectors that offer roughly 550 percent more flow than a stock nozzle, which allows us to achieve our desired fuel quantity in the shortest time and crank angle degrees possible.

Because the exhaust manifold on ’94-’02 Dodge trucks (second generation) centers the turbo mounting location and provides better spool up and drivability when added to ’03-present Cummins engines, Fleece took things a step further. Its all-inclusive Second-Gen Swap kits make adding the older style manifold and a T4 flange S400 a piece of cake

It seems common rail performance has caught up to the mechanical trucks in the drag racing scene for the most part, but do you think it will close the gap in the upper echelon of truck pulling?

CF: The common rails are competitive in the new PPL Limited Pro Stock Diesel Truck class (3.0 smooth bore). We can make the horsepower that the Super Stock class is making, but at that level, they can’t get all the power to the ground anyway, so it’s more about the experience and chassis setup at that point. Stay tuned … as a 2017 UCC (Ultimate Callout Challenge) competitor, I’m expecting to make 2,500 rwhp during the dyno challenge portion of the event.

What does the future hold for the FPE camp?

Fleece Brothers: We’re tooling up to build CNC-machined forged engine blocks in-house. We have the machine, material, and a good design that we’re ready to put into action. We plan to have the new block in our 300-inch dragster, and be ready for testing next spring.

We’re also in the process of designing a 40,000 square-foot facility with provisions for additional phases of growth. We expect to see another appreciable growth spurt with the newfound space as well as an increase in efficiency, and we plan to continue to offer the best-engineered components available for the diesel aftermarket.

We would like to thank Chase and Brayden for giving us the opportunity to sit down with them. For more information on Fleece Performance be sure to check out its website and Facebook page.

In addition to manufacturing turbos, CP3’s, tie rod sleeves, and other hard parts, Fleece offers a slew of products which are referred to as “problem-solver parts.” These heavy-duty, high-flow Allison transmission cooler lines replace the factory units on ’01-’10 Duramax powered GM’s that are prone to leaking.